Although haiku was known among

avant-garde circles in the West prior to World War II, the literary form did

not become familiar to a wider English-speaking audience until the late 1950s

and early 1960s. To a large degree, the

publication of two anthologies introduced haiku to the reading citizenry: Harold G. Henderson’s An Introduction to

Haiku in 1958, and Harold Stewart’s A Net of Fireflies in 1960.

Of the two, Henderson’s work is probably better remembered today and more widely available. Without taking anything away from Introduction’s continuing value through the decades, Fireflies deserves renewed attention.

There is nothing: there is everything. [1]

Whose thoughtless hand has broken off their limb.

--Chiyo-ni

Every flower I touch—a hidden thorn.

--Issa

Like goldfish undulating fins and tail.

--Getto

IRONICAL

How hot the pedlar, panting with his pack

Of fans—A load of breezes on his back!

--Kakô

How hot the pedlar, panting with his pack

Of fans—A load of breezes on his back!

--Kakô

The net is now, with no one at my side!

--Ukihashi

Has slashed, recedes the wild night-heron’s shriek.

--Bashô

My wild umbrella drives me back again.

--Shisei

Would be a streak of snow across the sky.

--Sôkan [3]

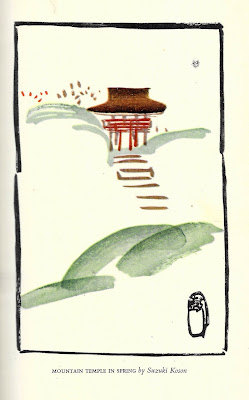

Mountain Temple in

Spring by Suzuki Koson

Autumn in a

Mountain Village by Ishikawa Kinichirô

Wintry Grove Under

a Waning Moon by Suzuki Rimpû [7]

A wide-ranging essay on the

essence of haiku occupies about a third of the book’s 150 pages of text on folded

leaves. Stewart expects a lot from the

writer of haiku, and his advice is as valuable today as it was in 1960. “The spontaneous conception and impromptu

expression required for a successful haiku are…a supreme test of poetic

concentration, conciseness and clarity.

The eye must always be on the object: the poet nowhere to be seen.” [8]

For its historical perspective as well as its continued relevance, A Net of Fireflies deserves a place on anyone’s haiku bookshelf. It is well worth the modest effort and cost to obtain a copy from the second-hand market. Ignore any paperback reprint; find a first-edition version, one with the green box cover as shown at the top of this article. The purchaser will not be disappointed.

[1] Stewart, Harold, A Net of Fireflies: Japanese Haiku and Haiku Paintings, Tokyo, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1960, 13

[2] The Los Angeles Times, January 10, 1961, III-5

[3] Stewart, Fireflies: More than Forgiven, 14; Return of the Dispossessed, 30; Dancers of Old Kyoto, 45; Ironical, 55; After the Death of Her Lover, 72; Double-Edged, 78; Contrary-Willed, 96; The Voice of Snow, 104

[4] The Indianapolis News, February 11, 1961, 2

[5] The San Francisco Examiner, February 12, Highlight, 7

[6] The Sacramento Bee, January 8, 1961, L14

[7] Stewart, Fireflies: Mountain Temple, 21; River Breeze, 42; Autumn in a Mountain Village, 67; Wintry Grove, 100. Artwork in the public domain.

[8] Ibid, 123—124

For its historical perspective as well as its continued relevance, A Net of Fireflies deserves a place on anyone’s haiku bookshelf. It is well worth the modest effort and cost to obtain a copy from the second-hand market. Ignore any paperback reprint; find a first-edition version, one with the green box cover as shown at the top of this article. The purchaser will not be disappointed.

[1] Stewart, Harold, A Net of Fireflies: Japanese Haiku and Haiku Paintings, Tokyo, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1960, 13

[2] The Los Angeles Times, January 10, 1961, III-5

[3] Stewart, Fireflies: More than Forgiven, 14; Return of the Dispossessed, 30; Dancers of Old Kyoto, 45; Ironical, 55; After the Death of Her Lover, 72; Double-Edged, 78; Contrary-Willed, 96; The Voice of Snow, 104

[4] The Indianapolis News, February 11, 1961, 2

[5] The San Francisco Examiner, February 12, Highlight, 7

[6] The Sacramento Bee, January 8, 1961, L14

[7] Stewart, Fireflies: Mountain Temple, 21; River Breeze, 42; Autumn in a Mountain Village, 67; Wintry Grove, 100. Artwork in the public domain.

[8] Ibid, 123—124

Russell Streur

A version of this article was originally published in Seashores, Volume 10, April 2023.

No comments:

Post a Comment